KID RENOUNCES THERAPIES, SURVIVES

Former “Therapy Mom

of the Year” tells

why she abandoned

therapies and held

on to her son.

by Kathie Snow

![]() or the first six years of my son Benjamin's

life, I could have won the prize for Therapy Mom of the Year.

or the first six years of my son Benjamin's

life, I could have won the prize for Therapy Mom of the Year.

If we weren't going to therapy, we were doing home programs. I moved the furniture out of our living room and bought therapy equipment, including a big orange therapy ball — the biggest! I had to inflate it indoors since it wouldn't have fit through the door.

A snapshot from those days shows my three-year-old daughter sitting one of her dolls on an eighteen-inch ball, doing what she saw being done to her baby brother. At the time, I thought it was so cute. Today it pains me.

I never doubted that what I was doing was right, even on the occasions when my son or I felt uncomfortable. I was sleepwalking through a mine field. My son, along with other people with disabilities, woke me up. I hope their

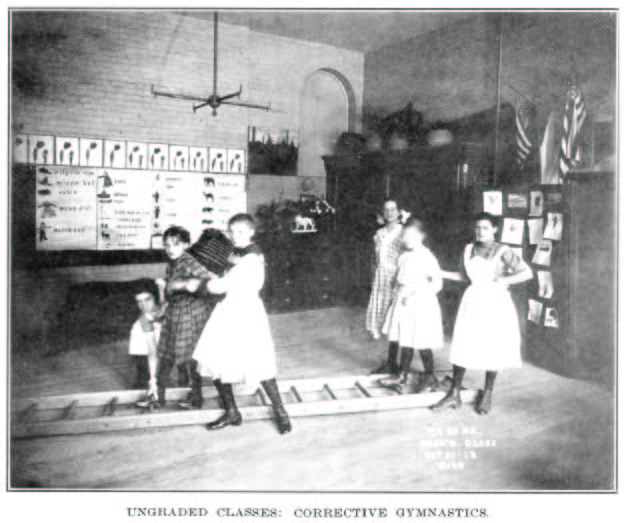

THE PHOTO OF CORRECTIVE GYMNASTICS USED THROUGHOUT THIS ARTICLE WAS PUBLISHED BY BUREAU OF EDUCATION EXPERIMENTS, BULLETIN #4, “EXPERIMENTAL SCHOOLS”: CHICAGO, 1917. THE BULLETIN IS PART OF THE JELLIFFE COLLECTION MADE AVAILABLE TO MOUTH THROUGH THE GOOD OFFICES OF DAVID MITCHELL AND SHARON SNYDER, UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT CHICAGO.

stories will wake up other parents too.

A caution before we go further: Some parents misinterpret my message. Let this be clear: I am not implying that we shouldn't help our children. I am saying (1) there are serious consequences for children and families in the therapeutic landscape, and (2) there are other methods we can use to help our children.

Furthermore, my observations are not an indictment of therapists. Most are good people. I loved some of my son's therapists like family. Even so, I have changed my mind about therapies.

![]() he helping hands of

he helping hands of

therapy can hurt the bodies and minds of our children, who are powerless to stop the pain. The pain is doubled when children feel their parents don't love them enough to protect them.

Traveling around the country to do presentations has enabled me to meet the true experts: adults with

PAGE 24 MARCH -APRIL 2002 MOUTH

The consequences of abandoning life in a therapeutic landscape

school — just one of the kids. Being a stay-at-home mom except when traveling, I drove my two kids to and from school every day, carting some of their friends along. Twice a week, Benjamin had therapy after school — once for OT, the other for PT. Every afternoon Benjamin asked, "Mom, do I have therapy today?" When I said, "No, not today," he yelled with joy and told me everything he wanted to do when we got home.

On the days when I replied, "Yes," he would respond with a dejected "Oh." After a couple of months of this, his response changed to, disabilities. Hearing their stories touched me — and also made me very uncomfortable when I was still Therapy Mom.

I would ask myself if Benjamin would spend years on a psychiatrist's couch because of what therapy was doing to him. Then I would argue with myself. "But if he doesn't get therapy, he'll never learn to walk or feed himself or transfer or sit up straighter or learn to write! He has to keep going!"

One day, though, I lis"I don't want to go today." Always I'd tell him why he needed to go. End of conver

tened to my son. His words sation. But his upsets over were like a magnet, pulling therapy day increased. He the stories I'd heard from began to cry and yell that he adults from the hidden didn't want to go. I assured recesses of my mind, creating him that I understood how he a powerful force I could no felt (yeah, right!) and told him longer ignore. he still had to go. I didn't

He was in first grade, in know it, but the end was near. an inclusive neighborhood One therapy day, he

If he didn’t get therapy, he’d never learn to walk

or feed himself or write. He had to keep going!

MARCH -APRIL 2002 MOUTH PAGE 25

exploded in tears and rage. I was accustomed to the tears by then, but the rage was new. Through near-hysterical sobs, with tears streaming down his six-year-old face, he shrieked, "I don't want to go any more, Mom! I've been going all my life and I'm not going any more! I just want to go home like the other kids.

“I want to be a regular kid!" Then he melted, crying uncontrollably.

![]() ow could I not respect his desire to control

his own life? It all happened in a split second, but it felt like a lifetime.

I took a deep breath, gathered my wits, and said, "Okay, Benj. If you

don't want to go any more, you don't have to. We'll find some other way for

you to get exercise, all right?"

ow could I not respect his desire to control

his own life? It all happened in a split second, but it felt like a lifetime.

I took a deep breath, gathered my wits, and said, "Okay, Benj. If you

don't want to go any more, you don't have to. We'll find some other way for

you to get exercise, all right?"

Grinning and wiping his snotty nose on his sleeve, he cheered up. "All right! Let's go home!"

When I told him that he'd have to face the therapist and tell her he wasn't coming any more, tears flowed again. "Benjamin," I told him, "this is your decision and I'm backing you up. But it's also your responsibility to tell the therapist." I was still hoping that what we'd decided was right. By the time we left, I knew it was.

He wanted to sit on my lap this time, with his arms around my neck, holding on tight to gather his courage. The OT stood five or six feet in front of us, waiting to take him into the therapy room.

His tears began again when he said it. "I'm not coming to therapy any more," he squeaked, then continued quickly before his bravery ran out. "I've been going to therapy all my life and I don't want to come any more. I just want to go home after school, like everyone else. And my mom says it's okay."

Big heaving sigh. He'd done it. The therapist's response was not unlike my own original replies to his

“I’m not coming to therapy any more,” he squeaked. pleas. Benj shook his head at her and strengthened his hold

“I’ve been going to therapy all my life.” on my neck. I'll make this

PAGE 26 MARCH -APRIL 2002 MOUTH

long story short: She tried to cajole him, she tried bribing him with new toys, she tried a variety of approaches. With each request, she moved a little closer. Benj continued to shake his head at her, maintaining his iron grip around my neck. A standoff was at hand.

That's when I learned

be at eye level with Benj, leaned toward him, and put her hand on his arm. He tried to move away, but he had no place to go, so he pushed back against me. I pushed further back too, but there was no way out. His hold on my neck was almost lethal. I never knew he had such strength.

Exasperated that every method had failed, she tried one last time. With her face inches away, her hand grip-ping his arm, she looked him in the eye and asked, "But Benjamin, don't you want to get well?"

Never had I told Benj that he was sick. Or had I? Did she really feel that he was sick?

I had heard enough. "We're going now," I told her. "You and I can talk about this on the phone."

That evening, she read me the riot act about ruining his life, throwing away six years of therapy, predicting that now he would get con– tractures. I got the message: I was an unfit mother.

I thanked her for all the good work she had done and signed off. Our family was finished with therapy.

![]() enj is a teenager now and neither he nor I

have regretted the decision he made at the tender age of six. When we reminisce,

he says, wistfully, "Going to therapy didn't make me feel like a regular

person."

enj is a teenager now and neither he nor I

have regretted the decision he made at the tender age of six. When we reminisce,

he says, wistfully, "Going to therapy didn't make me feel like a regular

person."

I apologize for making him go. He ends our dialogue with, "Well, Mom, I'm glad you finally listened to me, not the therapists and the doc-tors." >>>

what it must feel like to be a

child with a disability, to have

a powerful adult trying to That’s when I learned what it must feel like to have a

control you, with no means of

escape. She squatted down to powerful adult trying to control you.

MARCH -APRIL 2002 MOUTH PAGE 27

Our lives were irrevocably changed when we stopped therapy. Every member of our family felt such freedom! A sense of calm surrounded us. Tensions we thought were normal simply disappeared. Our lives were our own.

In hindsight, therapy was like a long-lost aunt who comes for a visit. At first there's excitement at the newness of it all. Then she decides to stay longer, then longer. When you finally tell her enough's enough, she goes home and you experience euphoria. You see life with new eyes.

![]() et's look at an adult therapeutic scenario.

Pretend I'm sixty years old and just had a stroke. I can no longer walk. I'm

right handed, but can no longer use my right hand. In the hospital,

at the rehabilitation center, and then in my home, the PTs will try to help

me walk again. The OT will attempt to restore normal function in my right

hand and arm.

et's look at an adult therapeutic scenario.

Pretend I'm sixty years old and just had a stroke. I can no longer walk. I'm

right handed, but can no longer use my right hand. In the hospital,

at the rehabilitation center, and then in my home, the PTs will try to help

me walk again. The OT will attempt to restore normal function in my right

hand and arm.

Therapy progresses. Weeks later, I'm beginning to be able to use my hand again but walking is harder. The PT thinks I should be making better progress. She redoubles her efforts.

I'm beginning not to like therapy any more. Perhaps I will never walk again. So be it. I'm ready to get on with my life. Get me a good wheel-chair and send me on my way.

The therapist is disappointed in my attitude. I'm not being very cooperative. She knows that if I will only try harder... And she tells the doctor what she thinks. He urges me to continue with therapy. I resist. They alternately encourage and berate me. I'm tired of all this. After a great deal of argument I convince the doctor to write a prescription for a wheelchair. It's my body, my life, my choice.

What’s it like not to be okay? Meet Susan. She’s Unlike adults, children

put on some weight since her marriage. are rarely permitted to exer-

PAGE 28 MARCH -APRIL 2002 MOUTH

cise their choice. Can therapy actually be harmful to children and their families?

And what unspoken messages do our children receive from therapy?

![]() ew of us eagerly anticipate visits to the

doctor or dentist. Is that because we

ew of us eagerly anticipate visits to the

doctor or dentist. Is that because we

able, and/or we don't like admitting that we're not okay at the moment. When we decide to see any health care provider, we're essentially saying, "I'm not okay." He or she replies, "That's right, you're not okay but I can make you okay." Certainly we think, "It will be over soon and then I'm done with it. I won't have to do that again for a long time."

Every time we take our children to therapy, we're sending them a very powerful unspoken message: "You are not okay."

What's it like to be not okay? Meet Susan. She's kind and loving, fun and friendly. She's put on some weight since her marriage to Dave sixteen years ago. At her 37th birthday party, Dave hands her a beautiful card. Inside it is a membership certificate to the local fitness center. Hurt, she asks what in the world he was thinking. He responds that he didn't mean to hurt her feelings. "A couple of times you said you wanted to lose weight. I thought I was helping!"

We don't send our kids to therapy because we're selfish and mean, any more than Dave is. We have been taught that if a person can't walk, talk, hear, feed himself — whatever he can't do — he's not okay.

In the deepest recesses of our hearts we may be hoping that therapy will take the disability away and our dream child will be restored to us. We may also be ashamed or embarrassed by the way our children look or act, and hope therapy will hate them or because we don't care about our health?

We don't like going for Deep in our hearts we may hope that therapy willany number of reasons: it's

embarrassing, it's uncomfort-take the disability away and restore our dream child.

MARCH -APRIL 2002 MOUTH PAGE 29

make our children more normal so we won't feel shame or embarrassment.

No matter why we do it, it's destructive.

I have not yet heard a child say she has internalized the not-okay belief. How many children could identify or explain that feeling? But adults with disabilities tell me that because they were taken to therapy all the time, they felt they were not good enough as they were. They must be sick, bad, abnormal. Why else would their parents make them go to therapy over and over and over again?

They also felt sadness and shame. They could not make the disability go away. They couldn't make their parents happy.

![]() have memories of stepping in to comfort

Benjamin when he became upset during a therapy session. How proud I've been

of what a great advocate I was for him. But I was brought up short recently

when Benjamin and Emily watched some old home moves, which included one of

Benjamin's therapy sessions. To my horror, I watched as he fussed and struggled

against the therapist. My voice is on the tape saying things like, "Benjamin,

stop fussing and listen to Mary." Or, "Benjamin, you don't need

to cry."

have memories of stepping in to comfort

Benjamin when he became upset during a therapy session. How proud I've been

of what a great advocate I was for him. But I was brought up short recently

when Benjamin and Emily watched some old home moves, which included one of

Benjamin's therapy sessions. To my horror, I watched as he fussed and struggled

against the therapist. My voice is on the tape saying things like, "Benjamin,

stop fussing and listen to Mary." Or, "Benjamin, you don't need

to cry."

I am ashamed of what I did. I'm saddened that I let my son down when he needed me to protect him, that I didn't accept him and feel pride in him as he was.

I discovered some scientific backup for questioning the effectiveness of therapy while I was researching a surgical procedure we were considering for Benjamin. I came across a research paper on physical therapy for children with cerebral palsy. I was shocked to read that the differences — between a group that had been in therapy for a year and an-other that had been in a preschool-like setting with no therapy — were negligible.

I had memories of being a strong advocate for my son. Parents have told me, "But

Then I got a look at some old home movies. I know therapy has helped

PAGE 30 MARCH -APRIL 2002 MOUTH

my child." No, we don't know that. When we see our children doing things now they couldn't do before, how do we know the child wouldn't have acquired the skill with or without therapy?

All children with disabilities have abilities, skills, and talents. Sadly, these are often overlooked by therapists and typical fashion or position his arm in the normal way, he's doing it "wrong." The goal of writing has been met, but therapy continues in an effort to make the child do it the "right" way. The message to the child is clear: you're still not good enough.

How many of us hold our pens and pencils the "right" way? How many of us write using the penmanship skills we were taught in school?

![]() y husband and I realized no one was

looking at Benjamin as a whole child. Therapists saw him in terms of body

parts that "didn't work right."

y husband and I realized no one was

looking at Benjamin as a whole child. Therapists saw him in terms of body

parts that "didn't work right."

One example: when he used his walker in first grade, everyone was thrilled with the longer and longer distances he could go. But when he walked to recess, by the time he got to the play-ground, recess was over and the other kids were running back inside.

Educators and therapists saw the progress made by body parts and were happy.

For a while, I felt the same way.

Excerpted from Kathie Snow’s book, Disability is Natural, avail-able through the Attitude Catalog and ©2001 BraveHeart Press, re-printed here with permission.

Snow also edits a newsletter,

Revolutionary Common Sense.

Subscriptions cost $16.95 from BraveHeart Press, PO Box 7245, Woodland Park CO 80863. Mouth recommends you subscribe and hopes you visit the website, www. disabilityisnatural.com.

parents because they're not done the "right" way. A child

has learned to hold a pencil

How many of us hold our pens and pencils

and write his name, but

because he doesn't hold it in a

the “right” way?

MARCH -APRIL 2002 MOUTH PAGE 31